International Students in the US

Forecasts from 2025-07-19 on visa issuance and enrollment

Higher education and immigration policy in the United States are both in flux. Six Samotsvety forecasters discussed a topic influenced by both of these factors: international student visas. We made forecasts on the following questions:

Will the number of new F-1 visas issued in (a) China and (b) India decrease by >10% in FY2025?

Will CS and engineering see a greater percentage decrease (or smaller increase) in the number of enrolled international students compared to other fields?

Will international graduate students decrease more (or increase less) than undergraduates?

Background

In recent decades, the US has taken in more international students than any other country. Higher education has been one of the primary routes for high-skill immigration into the US. Both international workers and American firms heavily rely on this channel — the former for the opportunity to work in the US, and the latter for the recruitment of high-skill labor.

Recently, the United States has been changing its approach to immigration, generally favoring more protectionist and nativist rhetoric and policy. We have seen:

High-profile visa revocations and deportations

New policies creating extra hurdles for international students, such as social media vetting and temporary suspensions of visa issuance

Increased funding and enforcement activities by immigration authorities (ICE)

Arbitrary SEVP (student permit) revocations

At the same time, universities have fallen out of favor with the government

Administration attacks on elite universities, most notably Harvard and Columbia

Proposed cuts to the NIH and NSF — major grant-making organizations — significantly impacting research funding

These suggest two paths to a reduction in the number of international students. The first is reduced demand, due to the US becoming a less appealing destination to study for both social and career reasons. The second are increased frictions, in the form of barriers that are erected in the way of willing students — lower visa approval rates, fewer visa appointments, higher revocation rates.

We discussed whether we expect a sharp decline in the number of international students in the United States, and how this might vary across different fields of study and levels of education.

Forecasts

Q1) Will the number of new F-1 visas issued in (a) China and (b) India decrease by >10% in FY2025?

Forecast:

(a) China: 76% (60-89%)

(b) India: 66% (50-84%)

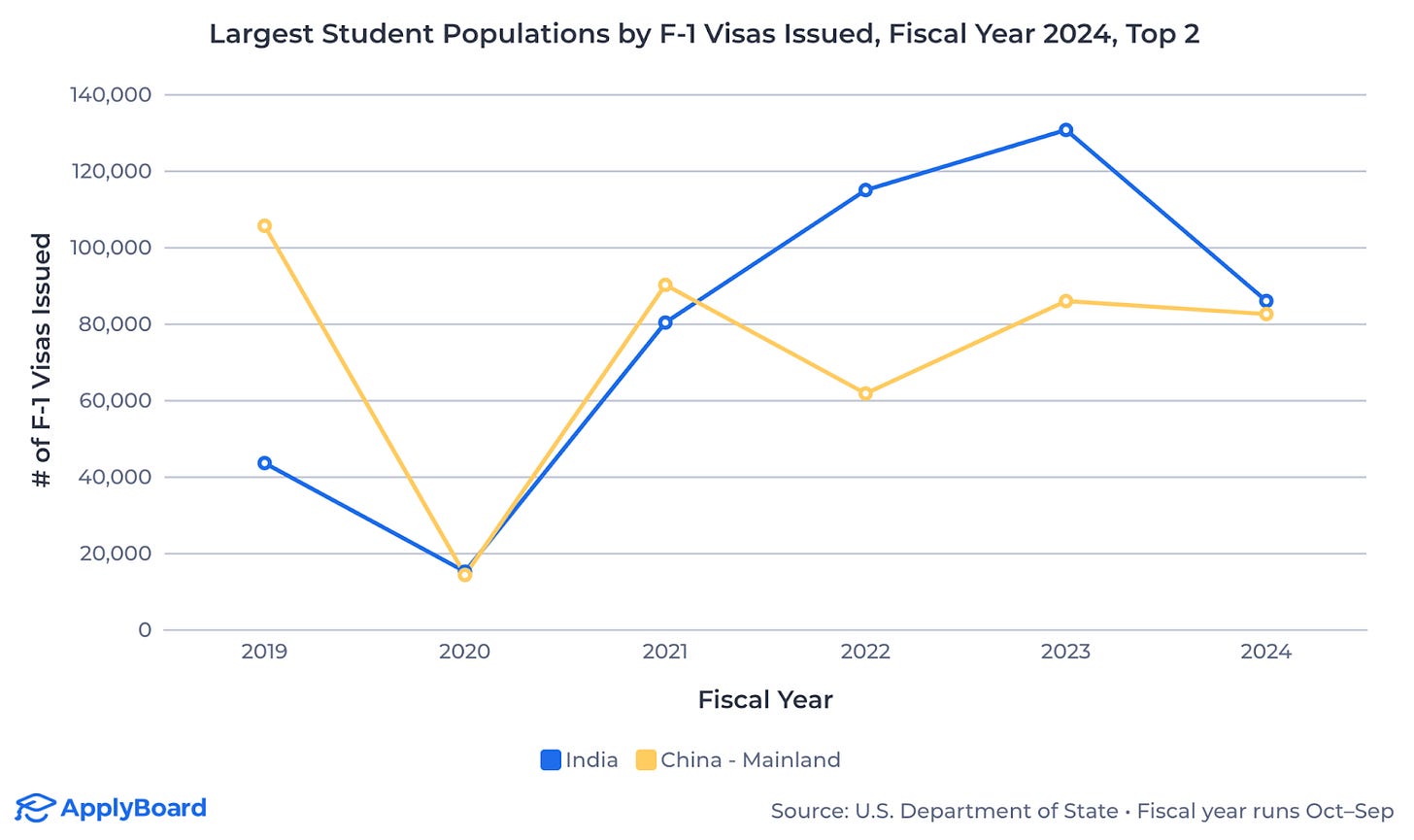

Chinese and Indian students make up approximately half of international students in the US. Since COVID, the number of Chinese students has been declining gradually, while the number of Indian students has been increasing. However, the number of new F-1 visas declined dramatically for both India and China in 2024, and has fallen further so far in 2025.

We estimate that a >10% decline in new F-1 visas in FY2025 has a 76% chance of occurring for China (60-89% across forecasters) and a 66% chance for India (50-84%). Given the volatility in annual visa issuance and the sharp declines in new F-1s in 2024, this change will likely fall within the normal range of variance in F-1 issuance, rather than marking a sudden paradigm shift. However, extended declines in new student visas could contribute to a longer-term shift away from the US as the Schilling point for international education and research.

Core reasoning:

As of May 2025, the number of new visas for FY2025 was substantially lower than FY2024 for both China and India. This decrease continued a trend from 2024, when new F-1 visa numbers dropped by 34% for India and 3.6% for China. In principle, this decline could be counterbalanced by a rebound during the summer, when the majority of new student visas are issued. But the lower visa numbers over the past year suggest that studying in the US has become less appealing. Actions by the Trump administration this year may accelerate this trend, making potential international students more cautious about studying in the US. Chinese students in particular may be wary in light of comments by the State Department about mass visa revocation for Chinese students.

On top of decreased demand, the visa interview freeze from May 27-June 18 blocked new visas for a large fraction of the peak season, limiting the time window for a potential rebound. We expect this to lead to a decrease in processed applications, and a lower number of new F-1’s overall. New rules for social media vetting may decrease the acceptance rate, though we believe this will have a smaller effect than the reduction in the overall number of applications.

A few sources of uncertainty limit the confidence of our forecast. The number of F-1 visas is volatile from year to year, particularly for individual countries. If last year’s change reflects a temporary drop rather than a sustained trend, baseline volatility and regression to the mean could lead to higher F-1 issuance in 2025, counterbalancing the effects of the visa freeze and new social media vetting. Universities facing funding challenges may also be incentivized to accept more international students, who often pay more in tuition than US students.

Q2) Will CS and engineering see a greater percentage decrease (or smaller increase) in the number of enrolled international students compared to other fields?

Forecast: 31% (25-35%)

Core reasoning:

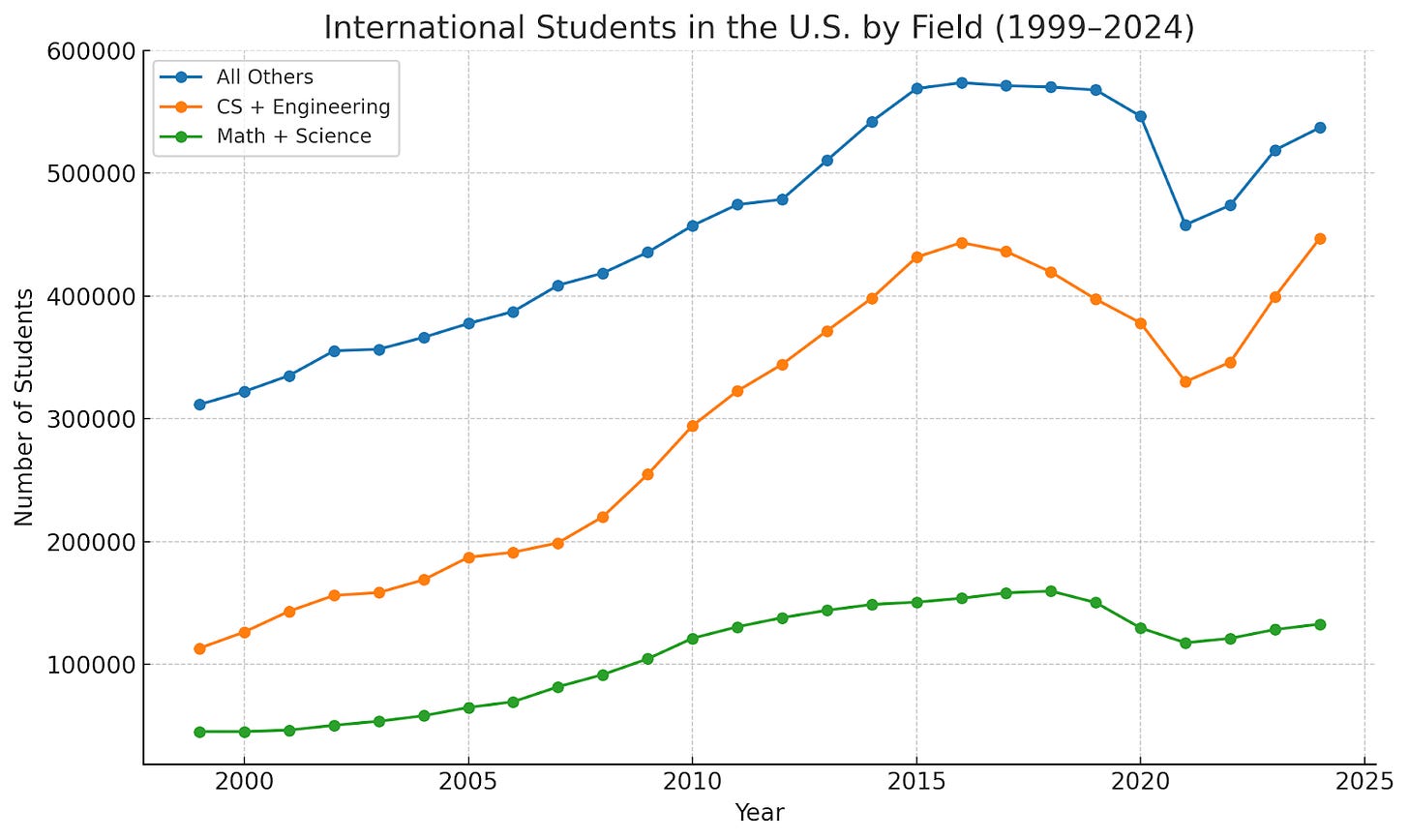

The number of international students in CS and engineering has been increasing faster than other areas for the past few years. In the absence of other factors, we would expect this trend to continue.

Shifts in US policy, particularly US-China relations, add some uncertainty to this trajectory. In May, the State Department declared that they would revoke visas for Chinese students “with connections to the Chinese Communist Party or studying in critical fields”, which seem to include subfields of computer science and engineering. China may also be more motivated to keep competitive students in the country, reducing brain drain in high-demand fields.

While these factors decrease our overall confidence, we don’t expect them to outweigh the baseline trend. The US is still seen as the best place to study many technical engineering fields, especially at graduate level, and demand for education in these areas may stay strong even if overall interest in a US education decreases. One forecaster also thought that social media screening might affect students in the humanities more than STEM fields, though we expect this to be a relatively minor influence overall. High enrollment over the past few years also provides a buffering effect for CS and engineering even if new visa issuance drops sharply, since current students will spend multiple years completing their programs.

Q3) Will international graduate student enrollment decrease more (or increase less) than undergraduates?

Forecast: 33% (25-40%)

Core reasoning:

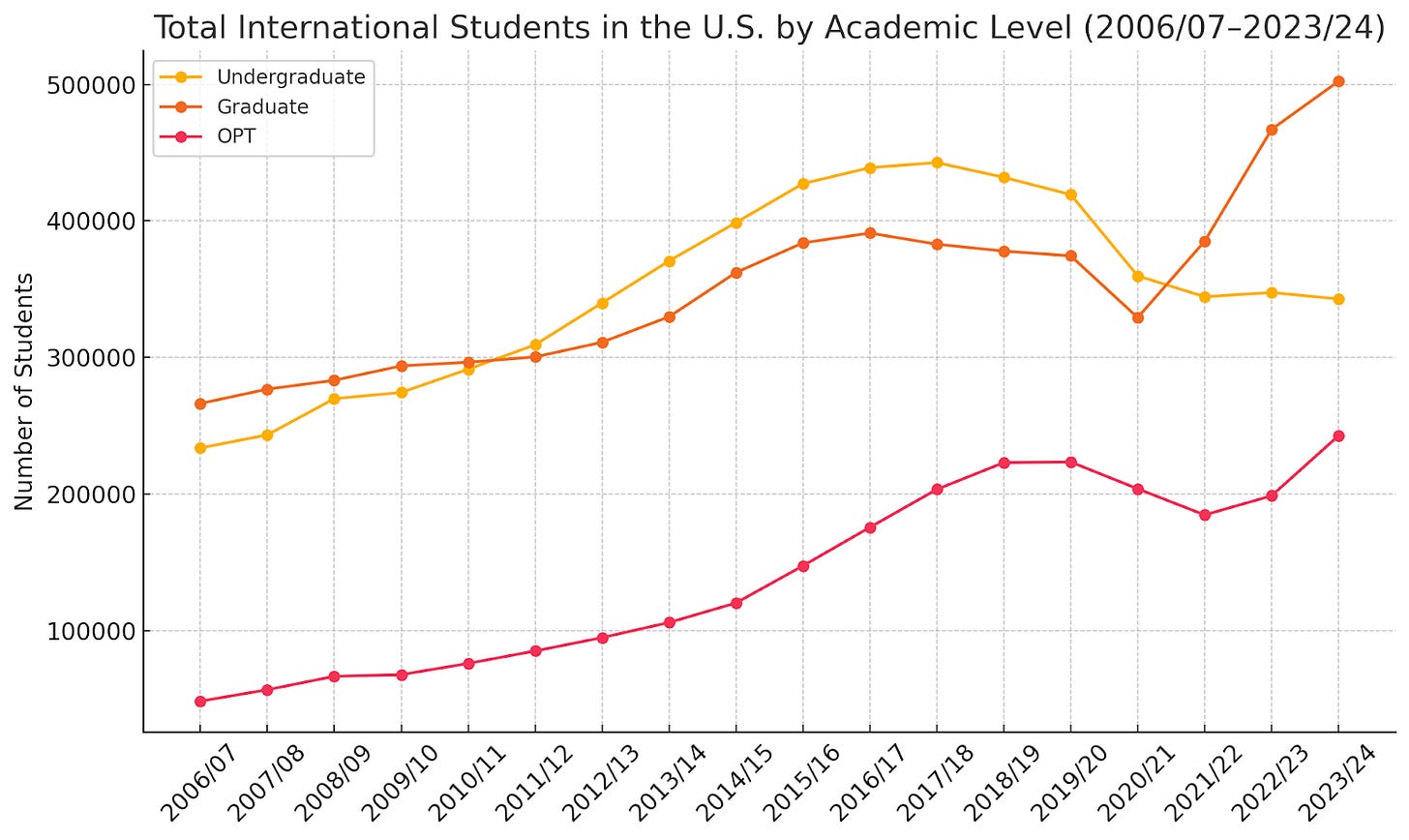

The number of international graduate students has been increasing more rapidly than undergraduates over the past few years, driven most strongly by master’s degree programs.

While we expect this trend to continue, a few factors put pressure in the opposite direction. Master’s programs tend to be shorter than undergrad degrees, so their enrollment numbers may be more sensitive to decreases in new F-1 visas. PhD programs are longer, but make up a relatively small fraction of students. They also rely heavily on federal grants, and will likely reduce new enrollments in response to recent cuts to research funding. The rise in graduate students is also relatively recent, and it isn’t clear how persistent it will be over the years

On the other hand, universities aiming to increase enrollment may have more flexibility to expand master’s programs, either by accepting more students or expanding options for undergraduates to transition directly into “fifth year master’s degrees”. Since direct undergrad-to-masters transitions avoid the need for a new visa, expansion of these programs could attenuate the effects of reduced visa issuance and increase enrollment numbers for graduate international students.